Chapter 1 Understanding Variation

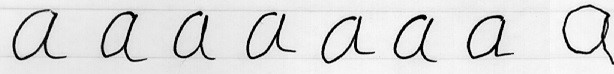

Imagine writing the letter a by hand using pen and paper. Figure 1.1 shows eight instances of this letter written by one of the authors. The first seven letters were produced with the dominant (right) hand, while the last one was written with the non-dominant hand.

Figure 1.1: Hanwritten a’s

Consider the seven leftmost a’s. Although these a’s were produced under identical conditions – same hand, date, time, place, pen, paper, temperature, lighting, and other factors – they are not identical. Instead, they exhibit controlled variation. This illustrates that a stable process, where the underlying conditions are the same, produces some degree of variation or “noise”. This controlled variation is known as common cause variation because it is caused by a stable process.

When examining common cause variation, one might be tempted to rank the letters, identifying some as “better” or “worse” and attempting to emulate the best while avoiding the worst. However, this approach is misguided. Because all seven letters were produced under the same conditions, no single letter is inherently superior or inferior. From the process perspective, these seven letters are equivalent, and their differences are attributable to common cause variation – variation intrinsic to the process itself. So how can we improve these a’s? To improve the quality of the a’s we should focus on modifying the process rather than trying to draw lessons from the differences between individual a’s.

To reduce variation and improve the quality of the letter a, we might consider changes such as using a different pen, paper, or training, or switching to a computer. Of these options, it is intuitive that using a computer will yield the most significant improvement. This insight is supported by the theory of constraints, which views a process as a chain of interconnected links. The strength of the entire chain is limited by its weakest link. Improving this weakest link will enhance the overall performance, while changes to other, non-constraint links, offer minimal benefit. In the context of handwriting, the weakest link is the manual use of the hand. The pen, paper, and lighting are not constraints in this process; altering them will not substantially impact the quality of the ‘a’. Switching to a computer addresses the key constraint, handwriting, resulting in a marked improvement in the quality of the letter.

Now consider the rightmost letter in Figure 1.1, produced with the non-dominant hand. Its marked difference from the others suggests a special cause. Special cause variation arises from factors external to the usual process and requires investigation. When encountering special cause variation, the response involves detective work to identify the underlying cause.

If the special cause undermines the quality of the process, efforts should focus on eliminating it. If the special cause enhances the quality of the process, then efforts should focus on trying to understand it and integrate it into the process where possible.

The handwritten letters exemplify the two types of variation:

Common Cause Variation: Intrinsic to the process, this variation is stable and predictable within a range. Addressing it requires systemic changes to the process as a whole.

Special Cause Variation: Arising from external factors, this variation is unstable and unpredictable and requires investigation. The response depends on whether the variation is beneficial or harmful.

The originator of this theory was Walter A. Shewhart, who, in the 1920s, sought to improve industrial product quality. Shewhart recognised that quality involves more than meeting specifications; it requires understanding and managing variation. He distinguished between chance cause variation, inherent to a stable process, and assignable cause variation, which results from specific, external factors (Shewhart 1931). Later, the terms common cause variation and special cause variation were adopted.

The various characteristics and descriptions of common and special cause variation are highlighted below.

| Common Cause Variation | Special Cause Variation |

|---|---|

| Arises from a stable, predictable system and is intrinsic to the process. | Arises from an assignable cause external to the process, making it unstable and unpredictable. |

| Reflects the normal behaviour of the process and affects all who are part of it. | Represents a distinct signal differing from the usual behaviour and requiring investigation to identify its cause. |

| Is neither good nor bad – it simply is. | May be favourable or unfavourable, and deliberate or incidental. |

| Can be reduced (but not eliminated) by changing the underlying process; such changes may be informed by special causes. | Unfavourable special causes can be removed; favourable ones can be adopted and incorporated into an improved process. |

| Also known as random variation, chance variation, natural variation, or noise. | Also known as non-random variation, assignable variation, systematic variation, or signal. |

In summary, statistical Process Control (SPC) revolves around understanding variation and identifying its causes – whether common or special – in order to drive meaningful improvement. Contrary to common misconceptions, SPC is not merely a method for spotting outliers; it’s a framework for enhancing processes and outcomes.

Statistical Process Control is not about statistics, it is not about ‘process-hyphen-control’, and it is not about conformance to specifications. […] It is about the continual improvement of processes and outcomes. And it is, first and foremost, a way of thinking with some tools attached.

– Wheeler (2000), p. 152

With this foundation in mind, most of this book focuses on the tools of SPC, particularly the SPC chart. In the next chapter, we delve into the “anatomy and physiology” of SPC charts, exploring their structure, function, and practical applications.